Do you imagine that the impact on kids will be due simply to the moms’ having more resources? Or is it more subtle than that? Perhaps they’ll be freed up to work less, have more time to bond and play?

You hit the nail on the head. We think that there are two main, measurable pathways through which the extra income is going to work: One is what we are calling the “investment pathway,” the idea that with more material resources, moms are going to be able to buy more books and toys, take more trips to the museum, afford better childcare and better housing in better neighborhoods. The other pathway is what we are calling the “reduced family stress pathway,” the idea that if moms are less worried about keeping the lights on or paying the rent, less in need of taking on that third job, that they’re going to be able to spend more time with their kids and be less stressed out when they’re doing it.

What does it mean for a new mom to worry just a bit less about money?

Well, we know that whenever someone is strained or stressed, they have less of what we call cognitive bandwidth, fewer mental resources to devote to everyday decision making. And that kind or strain can take the form of economic strain, or time strain.

How does that alleviating that strain impact the baby?

Moms are better able to manage the day-to-day pull of family life. Making sure they get their child to their well-baby checks or make that dentist appointment, better able to make family routines, reduce family chaos, which we know are all important for anchoring children’s development.

I wonder if some of the women in the trial might experience career growth during these three years.

It’s possible that their income will grow. It’s possible that it will simply stay steady instead of fluctuating. It’s also possible that the supplemental income will allow them to secure more career-building prospects, as opposed to patching together odd jobs.

What kind of leap can we make from your research to the potential impact of paid parental leave, if any?

That’s absolutely one of the things that we think there might be implications for in changing public policies. It was important to pick a dollar amount that could be feasibly informative to policy makers. The difference between those two amounts [$333/month vs. the control group of $20/month] is about equal to the earned income tax credit and other policy relevant social services that low-income moms may receive. If we know that increasing a mom’s income allows her to take more time away from the labor force shortly after having a baby and she’s therefore able to spend more time with that child in a warm and nurturing manner, we think that’s going to have cascading positive impacts on the children’s cognitive brain development.

I love that word, “cascading.”

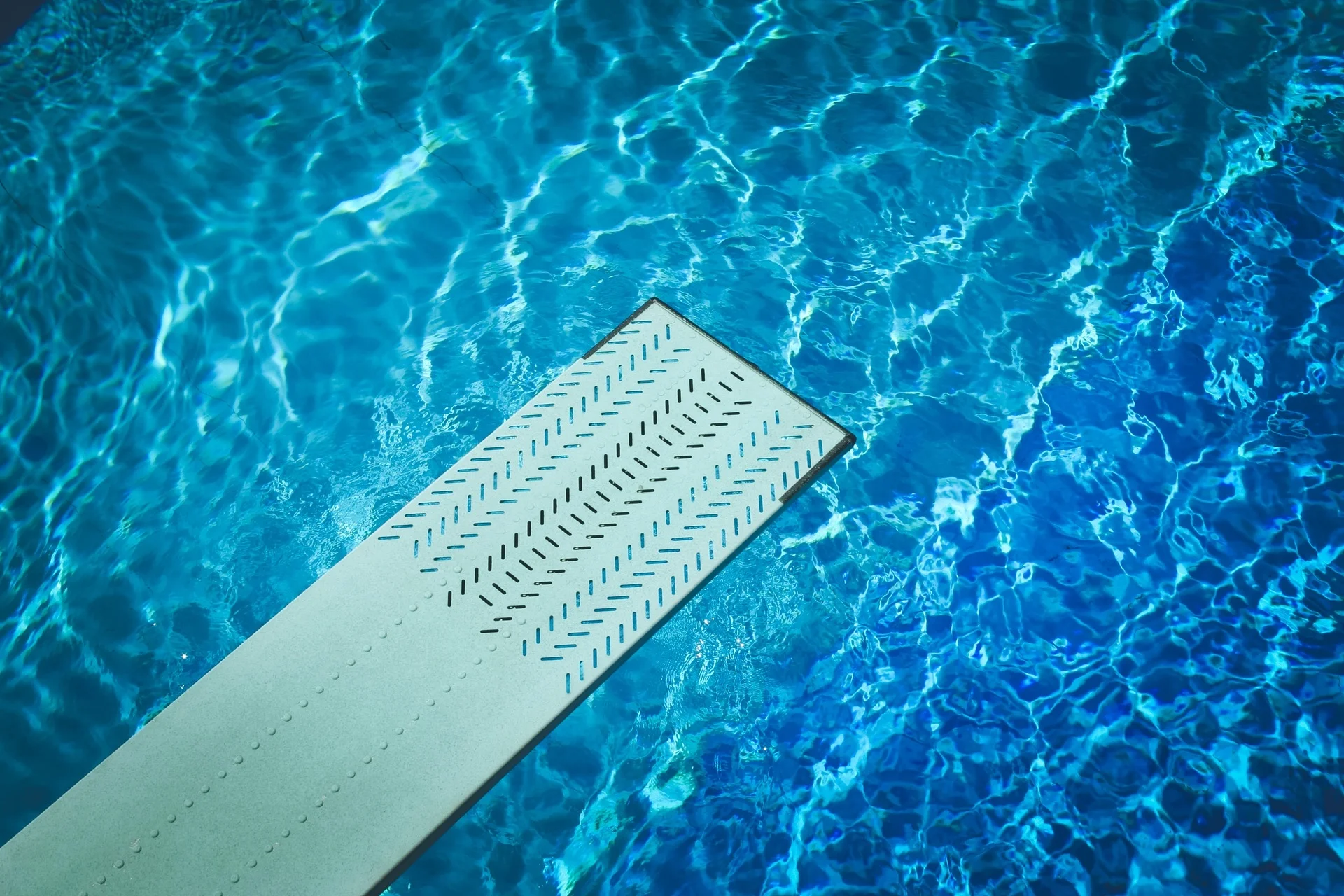

It’s a waterfall effect. Once it starts, you can’t stop it.

And it adds up, it pools, into something that only grows. Kind of like the potential impact of your research.

We hope so. We really want to make a difference.

Want to learn more, or donate to this research? Email Kim at kgn2106@tc.columbia.edu.